Quyen's Journal - A Vietnamese-American Volunteers in Vietnam

By Quyen Tran Witthuhn

Quyen Tran Witthuhn traveled with her sister, UyenThi, to Cao Lanh, Vietnam, as part of a Global Volunteers team teaching conversational English to children, teenagers, and adults.

Arriving in Vietnam

The plane touches down on Tan Son Nhat airport in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. As the plane rolls to a stop, I peer out the tiny airplane window for my first glimpse of Vietnam. I was born in Vietnam, but my family and I fled to the United States as refugees in 1975, when I was two years old.

I have no memories of Vietnam. And now, after 25 years of wanting to visit my birthland, after 25 years of thinking and saying "one day I'll go back and visit," I am in Vietnam.; I can't quite fathom that I am truly here. For 25 years,Vietnam was always over there, but now, it is here.

I see green grasses and waving palm fronds. I see remnants of old concrete

structures. Perhaps left over from the war? I may have been born

in Vietnam, but I realize that I perceive almost everything from the perspective

of an American. I grew up in Bloomington, Minnesota. Later I went

to high school in Chanhassen, home of the famed Chanhassen Dinner Theatre.

I enjoyed my college years at Macalester College in St. Paul. I'm as American

as they come, yet I am Vietnamese. And I've never felt so confused about

my identity until now, as I step onto the land of my ancestral roots.

I see green grasses and waving palm fronds. I see remnants of old concrete

structures. Perhaps left over from the war? I may have been born

in Vietnam, but I realize that I perceive almost everything from the perspective

of an American. I grew up in Bloomington, Minnesota. Later I went

to high school in Chanhassen, home of the famed Chanhassen Dinner Theatre.

I enjoyed my college years at Macalester College in St. Paul. I'm as American

as they come, yet I am Vietnamese. And I've never felt so confused about

my identity until now, as I step onto the land of my ancestral roots.

How to cross the street, Vietnamese style

On the taxi ride to our hotel in Saigon (as Ho Chi Minh City is still called by the locals) we are introduced toVietnamese-style traffic. It's absolutely marvelous to watch. Because almost everyone is on an efficient scooter, traffic jams are nonexistent. Traffic flows continuously and smoothly, like a school of fish -- crowded, yet fluid, with each person reacting to the vehicle ahead, beside, or behind. As scientists have observed, even chaos has a pattern.

I learn how to cross a street in Vietnam. Here, instead of waiting on one side of the street and looking both ways until it's safe to cross (if you did this, you'd never get to the other side!) you have to do as the locals do: that is, to walk -- in a very slow, meandering way - across the street. This gives the scooters, cyclists, cars, and cyclos enough time to gauge your speed and position, and thus zoom around and not into you. Do not run across the street, unless you have a death wish.

Here in Vietnam

After a steaming bowl of pho for breakfast (what heaven!) the Global Volunteers team rumbles off in a van for Cao Lanh, where the program is based. An up-and-coming town, it's located about 4 hours west of Saigon. It's also the city where my grandparents (on my mother's side) lived until their death.

I still marvel at the sheer coincidence of Global Volunteers' program being based in a city so near where I was born. Tram Chim (now renamed Tam Nong, as so many towns and streets were renamed after the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975) is where I was born, and it is only an hour and a half's drive from Cao Lanh. I vacillate between whether or not to go visit this town.

On the one hand, I tell myself, of course I must go! This is an unprecedented opportunity. To be in Vietnam, within acouple hours of where I was born? It would be foolish not to go. But part of me does not feel ready. I don't know if I'm emotionally not ready to see Tram Chim, or if I am just being superstitious. You see, I've been thinking up to now that this journey back to Vietnam is like having my life come full circle.

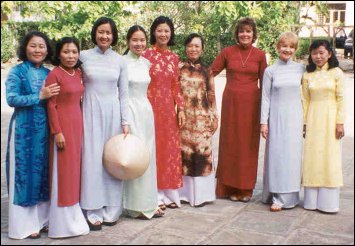

Many emotions run through me as scenes of everyday Vietnam speed past me on

the ride from Saigon to Cao Lanh. Children playing in the streets. Young

women dressed in the traditional ao dai. Old women selling fruit. The

buildings and homes built up one right next to the other. It's all everyday

life to them, but so different to me. And yet it could easily be me sitting

in the streets, selling fruit.

Many emotions run through me as scenes of everyday Vietnam speed past me on

the ride from Saigon to Cao Lanh. Children playing in the streets. Young

women dressed in the traditional ao dai. Old women selling fruit. The

buildings and homes built up one right next to the other. It's all everyday

life to them, but so different to me. And yet it could easily be me sitting

in the streets, selling fruit.

Another wave of emotion is felt for my parents. This all seems so strange to me. I feel a kind of relief that this is only a three-week program, and afterwards, I will be able to return to the comforts of home and my family. Yet 25 years ago, when my parents arrived with four small children in tow, they faced the same sheer unfamiliarity of a different country and culture, and knew they had to stay and live in that country forever. I grieve for my mom, especially Most of my dad's side of the family accompanied us, but my mother's parents, brothers, sisters,and homeland were all torn away from her and replaced by a land so foreign in language, climate, food, and people. I cannot even begin to imagine her shock and sadness. My mom never saw her parents again.

And what saddens me the most is that her story is not uncommon around this world. Not then, and not today.

My Parents' Friend in Vietnam

After morning class, UyenThi and I set out to find the one person in Cao Lanh that my parents told us to contact. We call her Co Ba, because she is the third child in her family. She and my parents used to teach at the same school in Tram Chim.

We have Co Ba's address, but it doesn't mean much here in Vietnam. By asking a succession of people if they know where Co Ba's home is, we are pointed further and further into a winding complex of unpaved alleys that connected small homes with the main road. Roosters crow even though it is ten-thirty in the morning. Women squat over fire pits, roasting corn, banana cakes, and other delicacies.

We finally arrive at the open door of Co Ba's home. An old woman, about four and half feet tall, wearing glasses, her hair neatly rolled into a bun, looks at us in a confused manner - my parents had not written to her beforehand. I clasp my hands and bow to her in the traditional Vietnamese greeting, and I introduce myself and UyenThi. I tell her my parents' name, and watch her eyes light up in amazement as she comprehends who we are.

She takes my hands firmly in hers, and leads us into her tiny house. We remove our sandals before entering, as is the Vietnamese custom. The floor is neatly laid with red tiles. Every inch of wall space is covered with icons of Jesus and Mary. A black and white TV perches on one shelf. A hammock, no more than five feet long, hangs from a metal stand.

In her house is young man of 22, whose education she sponsors. She raises money from family and friends, both from Cao Lanh and the U.S., and sends him to college to study computers. Other money is used for school supplies and clothes for small children in the rural areas surrounding Cao Lanh. Not for the first time on this journey, I am astounded and humbled by how a woman who has so little devotes her time to giving to those even poorer than she.

Evening Classes

My class in the evening is a bit different

from the morning one. The students are mostly teenagers, with a couple

adults. They stare at me for a while. Then one student asks me to write

my name on the board. I do so - Vietnamese style, last name first: Tran

Thi Hanh Quyen. There's another moment of silence. Finally, another

student asks, "Why do you have a Vietnamese name?"

My class in the evening is a bit different

from the morning one. The students are mostly teenagers, with a couple

adults. They stare at me for a while. Then one student asks me to write

my name on the board. I do so - Vietnamese style, last name first: Tran

Thi Hanh Quyen. There's another moment of silence. Finally, another

student asks, "Why do you have a Vietnamese name?"

I am stunned. So much for passing as a local! I realize I don't look Vietnamese to them. It must be my clothes (though they're all wearing western-style clothes) or my height (the average Vietnamese person seems to be about 5 feet tall).

I explain that I was born in Vietnam, and that my family and I came to the States in 1975 as refugees.

They ask, "Why did you leave?"

Not knowing how else to respond, I say, "Because when the war ended, we had to go."

As the class comes to a close, I can tell they still can't quite figure me out - am I American or Vietnamese?

Bartering and Shopping in Vietnam

In my various shopping excursions and rides on the pedicab (a bicycle towing a wagon on which the passenger sits), Idiscover that since I cannot pass as a local Vietnamese woman, I am being charged the higher price that foreigners are often charged (often double the local price).

When this happened the first time, my natural reaction was to bristle at what I thought was extortion. I would try to bargain the price down (bartering is a common practice in Vietnam). After successfully "saving" anywhere from 25 cents to a dollar, I began to feel rather foolish and ashamed of my stinginess; I started paying the asking price.

A Vietnamese Rural School

The team drove to a school about two hours from Cao Lanh, to deliver scholarships of notebooks, fabric for clothes, andmoney to 90 students. As our van pulls up, through the open windows of the classroom drift a few bars of a song the children are singing. With a start, I recognize the song from my childhood in Minnesota. As such memories are apt to do, the memory rips through my head and heart, and I try to connect and reconcile this live group of Vietnamese children singing, as they always have, with the faint echo of my mother singing the same song many years ago in Minnesota.

The Little Boy by the Bridge

There's a little boy whose mom sells peanuts near the river bridge by our hotel. Everyday when we walk past, the boy runs alongside, giggling and shouting, "Hello! Hello!" He holds up his hand for a high five. His fine black hair is cut short, but sticks straight up at the back of his head. He reminds me of my second oldest brother. His eyes and smile are strikingly similar.

Wedding Preparations in Vietnam

This morning I attended a wedding to which a student had invited me. First, we went to di ruoc dau - the ritual inwhich the groom and his family visit the bride's house and present her family with fruit, wine, and other gifts. The bride then accompanies the groom to his family's house, where more rituals are performed to honor their ancestors. Traditionally, the bride will live with her new husband and his parents for several years, until they can afford to move into their own house. If the groom is the youngest boy in the family, the couple will often live with the groom's parents until the parents die.

After much discussion over who will carry what to

the bride's house, I am given the top layer of the wedding cake - to carry with

one hand, in the rain, on the back of a scooter! Some of the roads are

greasy with mud, and I am doubtful of this proposition. Nevertheless,I grasp the cake stand and, bearing it like a torch, off I go on muddy, slippery

streets. I can't imagine this happening in the States! Any bride in the

U.S. would have a conniption if a stranger were given the top layer of the wedding

cake (complete with plastic groom and bride figurine) to transport in such conditions.

The scooter slips once in the mud, but there is only minor damage to the frosting.

The cake arrives safely and intact at the bride's house.

After much discussion over who will carry what to

the bride's house, I am given the top layer of the wedding cake - to carry with

one hand, in the rain, on the back of a scooter! Some of the roads are

greasy with mud, and I am doubtful of this proposition. Nevertheless,I grasp the cake stand and, bearing it like a torch, off I go on muddy, slippery

streets. I can't imagine this happening in the States! Any bride in the

U.S. would have a conniption if a stranger were given the top layer of the wedding

cake (complete with plastic groom and bride figurine) to transport in such conditions.

The scooter slips once in the mud, but there is only minor damage to the frosting.

The cake arrives safely and intact at the bride's house.

Another volunteer, Mary Ann, who also attends the wedding, has the unfortunate experience of asking for the bathroom at the bride's house. She is led to a little wooden stall built over the river. The floor is made of slats of wood, and a bucket of water and pail stand by, for rinsing the floor when you were done. The dishes are washed upstream, but further upstream, of course, is another house with another "bathroom." At the back of my mind, I always knew, of course, what went into that river, but it was never made so unfortunately explicit!

Tram Chim

We visited Tram Chim today. My emotions on this trip have overwhelmed me in sudden, unexpected upheavals. It happened as the plane was landing in Saigon and I saw my first glimpse of Vietnam. It happened in the van on the way from Saigon to Cao Lanh. And it happened today as I sat in front of the gutted buildings where my parents taught, met, and lived 30 years ago.

It takes us one and half hours to drive from Cao Lanh to Tram Chim by car. During my parents' time, there was no road, and same journey took them 6 hours by canoe. For the umpteenth time, I wonder what my life would have been like if my family had not left Vietnam. My father would probably have been sent to a "re-education camp," in other words, prison. I would probably be married, with children. Or perhaps I would be like the young teachers and students with whom Global Volunteers works. Maybe I would have attended a university and become an English teacher. If the course of events had run just a little differently, maybe I would've encountered Global Volunteers, but as a local teacher or student, instead of a privileged volunteer from the U.S.

It makes the head spin, all the might haves and could haves and what ifs. But this is all a worthless exercise, except to make me realize how fortunate I am.

What I Love about Vietnam

As we approach our final week in Cao Lanh, I delight in what I've come to love about Vietnam:

I love watching the eyes of the children in my morning class as they think of how to say "red" or "violin," and how their eyes light up when they know the answer.

I love riding on the back of a scooter, the breeze rustling through my hair and cooling my skin.

I love taking the pedicabs, or xe loi, at night, and gazing up at an entirely different sky of stars.

I love taking off my shoes before entering a home or shop.

I love being in a stranger's house, and having them pull out blotted pictures of my parents on their wedding day.

I love hearing stories about my parents when they were young, and hearing how I have my mom's dimples.

I love wearing my conical hat, the non la. I notice I attract less attention on the streets when wearing it!

Finally, I love to sit and watch the world pass by on the street: entire families on a scooter, a whole billboard on a pedicab, and young women in gracefully draped ao dai sitting upright on their bicycles, with not a speck of sweat on their nose.

On the Plane from Vietnam

I'm absolutely exhausted. But I'm at peace with my first journey back to Vietnam. It will be good to be back in Minnesota. That is, after all, where I have lived for 25 of my 27 years. Home is Minnesota, but a little bit of my head and heart will always remain in Vietnam.