Legacy of Operation Babylift

With the start of Operation Babylift, the number of children from Vietnam adopted in the United States and elsewhere rose dramatically.

Operation Babylift Lift Off

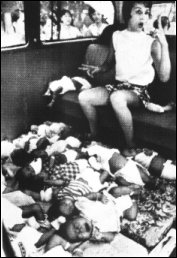

An immense cargo plane shuddered into the sky over Saigon. Inside the cabin, frightened toddlers and older children were strapped in with seat belts along the hard aluminum benches on each side of the aircraft. Down the center of the plane ran a row of 2-foot square cardboard boxes, each containing a precious cargo of two or three babies. A long strap stretched over the row of boxes securing them in place. Agency workers, Air Force personnel and volunteer parent escorts shook off their own fatigue and fear to scurry about trying to quiet the crying. Another flight of Operation Babylift had lifted off. Its cargo of orphan children had now left war torn Vietnam on their way to new lives in a distant country.

The Call for A Babylift

Two years after the United States signed a cease-fire with Vietnam, South Vietnam was crumbling under assault from the North Vietnamese troops. On March 30, 1975 South Vietnam's second largest city, Da Nang, was captured. By mid-April, Saigon was under attack from all three sides. Although several thousand American government officials and private citizens remained in Saigon, most of the other embassies were closed and their citizens had fled the country.

As North Vietnamese troops spread through South Vietnam, desperate, frightened people were pouring out of the country. Planeloads of refugees left Tan Son Nhut airport with greater frequency as soldiers closed in on Saigon. On April 27 alone, over 7,000 South Vietnamese refugees were flown out. When shelling rendered the airport inoperable, the signal (Bing Crosby's "I'm Dreaming of a White Christmas" played on Armed forces radio) was given for final evacuation by helicopter. Streets were mobbed with panicked Vietnamese people anxious to escape. During the last days of the withdrawal (April 29 - 30), more than 1,300 American and 5,500 Vietnamese people were flown out by helicopter from Saigon. Another 60,000 South Vietnamese people were rescued from rafts, fishing boats and cargo ships. All told, 132,000 southeast Asian refugees emigrated to the United States by the end of 1975.

In the final month before the fall of Saigon, the situation was deteriorating rapidly. Cherie Clark, the Friends of Children of Viet Nam (FCVN) representative in Vietnam, recalls that, "The country was collapsing around us, we had no idea what to expect at all. Provinces were falling like dominos and [Catholic and Buddhist] Sisters were running by boat and road to Saigon with the children they had found [who] were abandoned... [There was] virtually no money in the country. Milk was impossible to find, as was medicine. People were running by the plane loads out of the country. We could only think of survival..."

Humanitarian groups working with orphans in Vietnam were advocating that the American government undertake an emergency evacuation. With South Vietnam's reluctant agreement, President Gerald Ford announced on April 3 that Operation Babylift would fly some of the estimated 70,000 orphans out of Vietnam with $2 million from a special foreign aid children's fund. Thirty flights were planned to evacuate the babies and children.

With

the start of Operation Babylift the number of children from Vietnam adopted

in the United States and elsewhere rose dramatically. On April 3rd, a combination

of private and military transport planes began to fly more children out of Vietnam

as part of the Babylift. Numbers vary but it appears that at least 2,000 children

were flow to the United States and approximately 1,300 children were flown to

Canada, Europe and Australia. Service organizations coordinating flights including

Holt, Friends of Children of Viet Nam (FCVN), Friends For All Children (FFAC),

Catholic Relief Service, International Social Services, International Orphans,

and the Pearl S. Buck Foundation. In addition to the 4-7 day series of official

flights, smaller flights on chartered or loaned planes continued throughout

the month.

Tragedy Strikes

Tragically, one of the first official government flights of Operation Babylift

was struck down by disaster. A C-5A Galaxy plane - at that time the largest

airplane in the world - departed with more than 300 children and accompanying

adults. 40 miles out of Saigon and 23,000 feet up in the air, an explosion blow

off the rear doors of the giant craft. The flight controls were crippled and

decompression filled the plane with fog and a whirlwind of debris. Few could

get to oxygen masks as the overcrowded transport aircraft had been prepared

for 100 children, rather than the 300 passengers who had ultimately been loaded

aboard.

In what has been called "a remarkable demonstration of flying skill,"

the US Air Force pilots were able to turn the plane back toward Saigon. The

damaged plane crash landed 2 miles from Tan Son Nhut airport. It skidded about

1000 feet, bouncing up again for about half a mile, and then hit a dike and

broke into several pieces upon final impact. Parts of the plane burned nearby,

coated with oil from the crash. Rescue helicopters arriving quickly from Saigon

were unable to land in the water of the surrounding rice paddies. The crew members,

nurses, and volunteers (some of them wounded themselves) waded through the mud

carrying the children to the helicopters hovering nearby. They had to shield

the wounded with their bodies as winds from the helicopter rotors tossed the

aircraft debris and smoke though the air.

Sadly, in what was one of the worst aircraft disasters in history at the time,

more than half of the children and adults aboard the craft died. Almost everyone

in the bottom cargo compartment was killed - the majority were children who

were 2 years of age and younger. Seven FFAC adoption volunteers were killed

in the crash, along with service members. Many of the 170 or so survivors were

injured. Among those who survived unscathed was a baby (Melody) who was profiled

in the press because of her subsequent adoption by actor Yul Brynner.

Little Time to Mourn : The Flights Continue

Many people in the United States viewed the Galaxy crash as another in a long

series of tragic events surrounding the ill-fated war in Vietnam. At Tan Son

Nhut airport, there was no time to mourn, for the fall of Saigon was near. A

Pan American Airways Boeing 747 chartered by Holt International that day carried

409 children and 60 escorts, apparently the largest planeload of the Babylift.

Reports vary, but it appears that 1200 children were evacuated in the 24 hours

following the Galaxy crash, including 40 of the surviving children.

With

the start of Operation Babylift the number of children from Vietnam adopted

in the United States and elsewhere rose dramatically. On April 3rd, a combination

of private and military transport planes began to fly more children out of Vietnam

as part of the Babylift. Numbers vary but it appears that at least 2,000 children

were flow to the United States and approximately 1,300 children were flown to

Canada, Europe and Australia. Service organizations coordinating flights including

Holt, Friends of Children of Viet Nam (FCVN), Friends For All Children (FFAC),

Catholic Relief Service, International Social Services, International Orphans,

and the Pearl S. Buck Foundation. In addition to the 4-7 day series of official

flights, smaller flights on chartered or loaned planes continued throughout

the month.

Tragedy Strikes

Tragically, one of the first official government flights of Operation Babylift

was struck down by disaster. A C-5A Galaxy plane - at that time the largest

airplane in the world - departed with more than 300 children and accompanying

adults. 40 miles out of Saigon and 23,000 feet up in the air, an explosion blow

off the rear doors of the giant craft. The flight controls were crippled and

decompression filled the plane with fog and a whirlwind of debris. Few could

get to oxygen masks as the overcrowded transport aircraft had been prepared

for 100 children, rather than the 300 passengers who had ultimately been loaded

aboard.

In what has been called "a remarkable demonstration of flying skill,"

the US Air Force pilots were able to turn the plane back toward Saigon. The

damaged plane crash landed 2 miles from Tan Son Nhut airport. It skidded about

1000 feet, bouncing up again for about half a mile, and then hit a dike and

broke into several pieces upon final impact. Parts of the plane burned nearby,

coated with oil from the crash. Rescue helicopters arriving quickly from Saigon

were unable to land in the water of the surrounding rice paddies. The crew members,

nurses, and volunteers (some of them wounded themselves) waded through the mud

carrying the children to the helicopters hovering nearby. They had to shield

the wounded with their bodies as winds from the helicopter rotors tossed the

aircraft debris and smoke though the air.

Sadly, in what was one of the worst aircraft disasters in history at the time,

more than half of the children and adults aboard the craft died. Almost everyone

in the bottom cargo compartment was killed - the majority were children who

were 2 years of age and younger. Seven FFAC adoption volunteers were killed

in the crash, along with service members. Many of the 170 or so survivors were

injured. Among those who survived unscathed was a baby (Melody) who was profiled

in the press because of her subsequent adoption by actor Yul Brynner.

Little Time to Mourn : The Flights Continue

Many people in the United States viewed the Galaxy crash as another in a long

series of tragic events surrounding the ill-fated war in Vietnam. At Tan Son

Nhut airport, there was no time to mourn, for the fall of Saigon was near. A

Pan American Airways Boeing 747 chartered by Holt International that day carried

409 children and 60 escorts, apparently the largest planeload of the Babylift.

Reports vary, but it appears that 1200 children were evacuated in the 24 hours

following the Galaxy crash, including 40 of the surviving children.

Getting the children to the airport was quite a feat

given the growing panic in the streets. For the air crews, agency personnel

and parent volunteers who accompanied the children though, boarding the planes

was just the beginning. LeAnn Thieman, who was on one of these planes as a volunteer

parent escort for 100 babies, describes the scene after take off in her inspirational

book, "This Must be My Brother":

Getting the children to the airport was quite a feat

given the growing panic in the streets. For the air crews, agency personnel

and parent volunteers who accompanied the children though, boarding the planes

was just the beginning. LeAnn Thieman, who was on one of these planes as a volunteer

parent escort for 100 babies, describes the scene after take off in her inspirational

book, "This Must be My Brother":

"The commotion of loading and transporting babies had not allowed (us) time to feed them. Now all ninety were awake and crying simultaneously... We discovered we could feed all three babies in a box at the same time by placing them each on their side and propping their bottle on the shoulder of their box-mate. Some sucked the formula down in only minutes, while others needed more help. I cradled a baby girl on my folded legs and coaxed her to drink while using my left hand to feed another baby in the box. The nipple fell from the mouth of the baby on my lap. Clearly she was too weak to suckle. Using both hands, I milked formula from the nipple to drop into her mouth...."

Upon Arrival...

The children were airlifted to countries where many people preferred to forget the traumas of the Vietnam War. Yet these children received a tremendous welcome. For example, Ian Harvey in a 1983 study of adoptions from Vietnam in Australia, reported that, "Once the news of the impending evacuation of Vietnamese children became known in Australia there was a rush of adoption applications". In New South Wales where 14 children were available for open adoption, an astonishing 4,000 applications were mailed out in response to telephone inquiries and 600 were returned. In the United States, volunteers for adoption groups reported that the phone rang off the hook for days with calls from perspective parents.

Miriam Vieni, a US social worker and adoptive parent, remembers:

"That morning (of the crash), many of the mothers from our FCVN adoptive parents support group gathered at my house. I made coffee and they brought cake and cookies, and we had what amounted to a wake. Suddenly the phone began to ring and people were asking about adopting babies. A Newsday reporter had written an article about the Vietnamese babies and for some reason he gave my phone number and my address as the phone and address of the FCVN agency. Not only did the phone not stop ringing, but people began coming to the door."

"The people who called and came, had this fantasy that there were all these Vietnamese babies just waiting for people to pick them, and they had suddenly gotten this great idea that it would be nice to have one of these cute Asian babies. The fact was that the babies had already been assigned to families and were just waiting for processing. The "Baby Lift" was a way of removing them from a dangerous situation without the usual processing, but they actually went to the families who had been approved and were waiting."

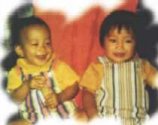

Pat and Dave Palmer, adoptive parents from Iowa, were processing their paperwork at the time. Pat describes the commotion around the placement: "When we applied to adopt a second Vietnamese baby, we had to really hurry the application along due to the uncertain political situation of early 1975. Our homestudy was completed and on its way to [our agency] FCVN in Denver just as the Babylift was getting underway. At that time it was impossible to reach the agency by phone because the agency's lines were jammed with calls from people who suddenly decided they'd like to adopt a Vietnamese orphan due to all the Babylift publicity. I had to send a telegram to notify FCVN that our approved homestudy was in the mail and that we would adopt a boy or a girl.James was offered to us after he arrived in the US on the Babylift. He was about a year old and the dearest little boy. He has added so much to our family."

Operation Babylift Controversy

However, the adoption of these children was also accompanied by controversy. There was a rather publicized debate as to whether the children were "better off" in the United States or in the country of their birth. Some of this was true concern, some was perhaps unacknowledged racism, and some was a reflection of emotions related to the war. Criticism and hostility came from both ends of the American political spectrum.

"Charges were made that removing children from their homeland and depriving them of their birth culture was American Cultural Imperialism. Some people insisted that the Vietnamese could have cared for the children had they been left in Vietnam. There were people opposed to transracial adoption. On the other hand, there were discussions on TV as to why people weren't adopting African American waiting children in the U.S.,"Miriam Vieni explains.

One of the biggest controversies surrounding the Babylift was the circumstances in which some of the relinquishments occurred. Documentation for many of the children was one of the casualties of the war and its aftermath: concerns were raised over lost or inaccurate paperwork. In several cases, birth parents or other relatives who immigrated to the United States requested custody of children already placed. A widely reported class action lawsuit in California, which contended the children were "taken from South Vietnam against the wills of their parents," resulted in delays in citizenship approval for some families. In 1976, the Des Moines Register reported that, "A year after they arrived by the planeload from embattled South Vietnam, hundreds of "Operation Babylift" children remain under a murky legal status in this country. And, more important, the Americans who took the young refugees into their homes still are uncertain about whether the children are really theirs to keep and rear." However, despite the turmoil surrounding some adoptions, many others

were unimpeded. Pat Palmer recalls that, "Although we didn't receive any

papers for James until about six months after he joined our family, we had no

doubt that he had been in an orphanage for some time before being placed on

the Babylift. James was slightly malnourished, had scabies, was very weak and

yet could walk by holding on to furniture, and loved nothing better than to

be held. We did not have any problems legally adopting him, nor did we have

any difficulties when we applied to have him naturalized along with our older

Vietnamese son, Rob."

However, despite the turmoil surrounding some adoptions, many others

were unimpeded. Pat Palmer recalls that, "Although we didn't receive any

papers for James until about six months after he joined our family, we had no

doubt that he had been in an orphanage for some time before being placed on

the Babylift. James was slightly malnourished, had scabies, was very weak and

yet could walk by holding on to furniture, and loved nothing better than to

be held. We did not have any problems legally adopting him, nor did we have

any difficulties when we applied to have him naturalized along with our older

Vietnamese son, Rob."

Not all of the children adopted during this time were babies and toddlers. Many were older, most likely even older than the ages given. Some of these older children had significant issues related to the relinquishment, attachment, and emotional reaction to the overwhelming events of loss and change. Additionally, according to Ian Harvey in Australia, "Most of the 'airlift' children were suffering from some illness, trauma, malnutrition or other deprivation on their arrival..." Some of the babies were ultimately too weak and sick to survive.

Looking Back on Operation Babylift

Over time, most adoptees appear to have successfully integrated into their families and into their new countries. The 1983 Australian study reported that in New South Wales over 90% of families who adopted Vietnamese children felt that the adoption was "successful" or "very successful" for themselves, the family, and the child. Parents of children over 4 years old reported more behavioral difficulties. The study concludes, however, that while many of the adopted children were originally described by pediatricians as 'emotionally deprived', by the second or third year after adoption, most "had become stable in health, secure within their families, and exhibited behavior acceptable for a child of that age."

The babies and children who were brought over on Operation Babylift are now in their mid 20's and 30's. From e-mail traffic to Vietnam adoption support groups it appears that many adoptees continue to wonder about their past lives before the airlift.James Palmer, who was adopted as a baby (above) is now a secondary teacher for the Minneapolis School District. He describes his mixed feelings, "Really the Vietnam War is not a part of my life. And yet, it probably had more impact on my life than almost anything else." Although he is content about his Asian heritage, James wonders about his birthparents, "I really want to know what they looked like, what their personality was.I picked up a lot from my mom and dad, but some traits are just genetic. Sometimes I get emotional about it."

Cherie Clark, currently the director of the International Mission of Hope in Vietnam, is writing a book which will address some of the questions she receives about the Babylift. She corresponds with a number of adoptees and, in some cases, has provided assistance in tracing documentation, orphanages, towns, even friends or relatives. "I have a huge number of children that I have placed over the years who are adults that I write back and forth to," Cherie Clark says. "One message I try to convey is that if you made it to the point that you were adopted then someone cared along the way very much about you. The lives of these children are so fragile that if someone doesn't really care then there is simply no way that they could have survived... Each child is different and some simply just need more to survive. But they all need care and love to make it to some point in their life no matter who they are adopted from or through. Sometimes this is all that I have to give to some of the older children - the sense they were cared for and loved."

Looking Forward from Operation Babylift

During the time of Operation Baby Lift, more than 2,000 babies and children were flown out by military and private planes to be adopted by families in the United States. It is astonishing that more children were adopted in the United States from Vietnam during this short, dramatic interval than the total for the past 24 years.

In the 15 years following Vietnam's unification, only 44 Vietnamese children were adopted by Americans. However, adopitons did resume over time. the United States reopened diplomatic relations with Vietnam in 1995: the number of adoptions from Vietnam to the United States doubled that year. Adoptions continued to increase each year, doubling again in 1998, when 603 children were adopted from Vietnam in the United States.Conclusion

The people involved in the Babylift, almost 25 years ago, responded from their hearts to the babies and young children who were casualties of the finale of the Vietnam War. Many of these people responded in exceptional ways - religious workers who took great risks to bring children to the centers for evacuation; the parents who made a commitment to adopt these children; the birth parents who trusted their children to an uncertain fate; and finally the agencies and volunteers who worked around the clock on adoption papers. Together they facilitated a new beginning for adoptees and adoptive families - a generation that we are blessed to have with us today.